Cuba seeks to control fake news

National Assembly of People’s Power approves Social Communication Law

The National Assembly of People’s Power has taken a step toward controlling fake news in Cuba. It approved on May 25 a law mandating that information disseminated by state entities, mass organizations, media organizations, news agencies, radio, television, social media, natural persons, among others, must be truthful, objective, appropriate, current, verified, and understandable.

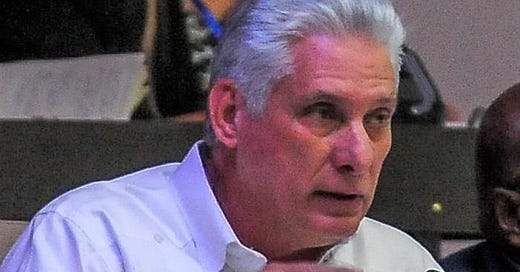

The National Assembly of People’s Power is the highest constitutional and legal authority in Cuba. Its 470 deputies are elected by the people in referendum style, as single candidates on the ballot, following their nomination by the delegates of the 168 municipal assemblies of people’s power, who have been elected from two or more candidates in elections held in 12,428 voting districts, who in turn had been nominated directly by the people through a series of neighborhood nomination assemblies. The National Assembly of People’s Power not only makes laws; it also has the authority to elect and reca…