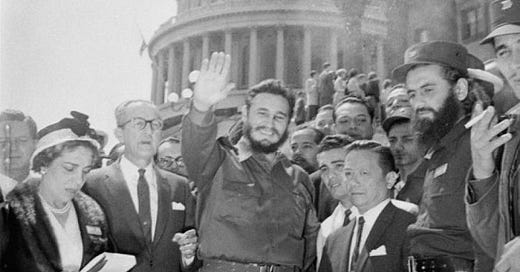

Sixty-five years ago, four and one-half months after the triumph of the Revolution, Fidel undertook a trip to the United States of eleven days, from April 15 to April 25, 1959. We were reminded of this fact by Elier Ramírez Cañedo and René González Barrios in an article published on April 17, 2024, “In the Name of Hope,” in the Cuban internet news outlet Cubadebate. Ramírez is a Cuban academic who is the co-author of a book on the policy of the United States toward Cuba; González is the Director of the Fidel Castro Ruz Center.

I like the way Ramírez and González describe the historic moment. “The triumph of the Cuban Revolution on January 1, 1959, was an earthshaking event for the absolute hegemonic dominance of the United States in the Americas. The model of bilateral relations of total dependence was broken and a political, economic, and social project was born, alien to the templates of global capitalism…