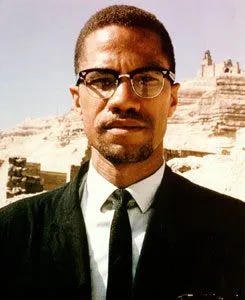

In his autobiography, Malcolm X said that whites concerned about racial injustice and racial inequality should work among their own people, seeking to educate white society.

I took Malcom’s advice to heart, as a personal commitment to the black community. From 1973 to 2010, as a professor of sociology in four colleges in the USA (East, Midwest, and South), I taught courses in the political-economy of the world-system, racial and ethnic relations, social inequality, and social movements. The course on political economy, which was of my own creation, covered the historical development of the modern world-system on a colonial foundation; and the twentieth century Third World anti-colonial movements that the world-system generated. It was complemented by two experiential courses, also of my own creation, involving educational travel in Honduras and Cuba. My students were overwhelmingly white middle class. I had to relocate a couple of times, because the anti-coloni…