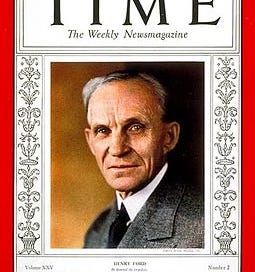

In my last commentary on April 11, I focused on Henry Ford’s method of manufacturing, involving continuous improvement in the process of production of the product, with the intention of producing an affordable, high quality, and durable product in response to consumer needs and desires; and involving the highest wages that the market can manage combined with modest dividends for workers-stockholders. In today’s commentary, I continue my reflections on Henry Ford, focusing on Ford’s comments with respect to war, imperialism, and neocolonialism, which I find progressive by today’s standards.

§

On War

Writing in 1922, Henry Ford maintained that World War I made evident the “great number of defects in the financial system” as well as the insecurity of a business community that exists on the foundation of the pursuit of money instead of the pillars of advanc…