Ho Chi Minh discerned that it was not a question of class exploitation versus national domination. He understood that there is a double axis of domination, in which both class exploitation and national domination are intertwined, and that liberation requires the transformation of both forms of domination. Furthermore, Ho understood that the whole world was in need of liberation, and that the full liberation of the workers of the West would require their solidarity with the Third World anti-colonial movements of national liberation.

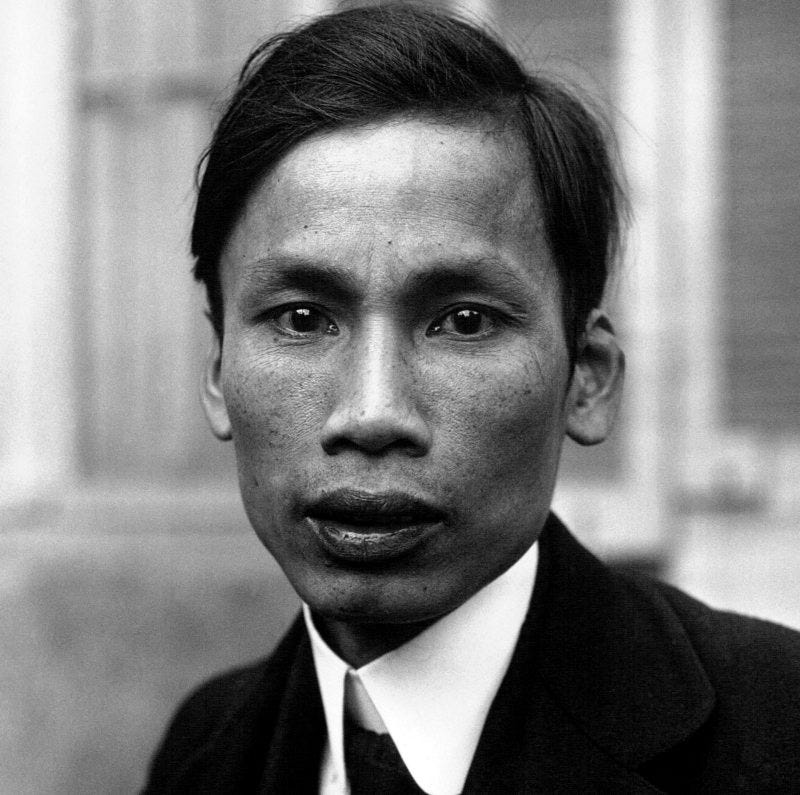

The forming of Nguyen the Patriot

Nguyen Sinh Cung, the original name of the historic figure known as Ho Chi Minh, was born on May 19, 1890, in the protectorate of Annam in French Indochina. His father, Nguyen Sinh Sac, became a Confucian scholar, even though he came from a family of poor peasants. After years of study and…