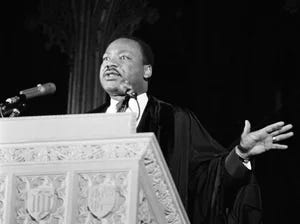

Let us honor Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. by remembering what he taught and rethinking his teachings in the context of the challenges of the nation and the world today.

Dr. King emerged to become an important moral authority on the national and world stage from 1955 to 1965, as a leader of mass actions in the U.S. South demanding civil and political rights for all citizens, regardless of race, with a secondary focus on the need for the full protection of the socioeconomic rights of all citizens. The southern civil rights movement triumphed, leading to fundamental changes in U.S. laws and customs with respect to civil rights, voting rights, and access to public accommodations. The triumph was made possible by the intelligent strategies of the movement, which focused on specific and clear demands, connecting them to the fundamental Jeffersonian principles of the American Republic. It was aided by the fact that the United …