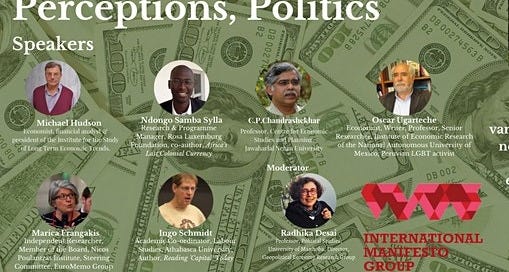

On May 13, 2022, the International Manifesto Group sponsored a Webinar on “The Return of Inflation.” The panelists included: Michael Hudson, financial analyst and president of the Institute for the Study of Long Term Economic Trends, distinguished research professor of economics at the University of Missouri–Kansas City, and professor at the School of Marxist Studies, Peking University, in China; Ingo Schmidt, academic coordinator of the Labour Studies Program at Athabasca University, Canada; Marica Frangakis, a member of the board of the Nicos Poulantzas Institute, Athens, and a member of the Steering Committee of the EuroMemo Group (European Economists for an Alternative Economic Policy in Europe); Ndongo Samba Sylla, Researcher and Programme Manager for the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation; C. P. Chandrashekhar, professor at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi; and Óscar Ugarteche, economist, professor and Senior Researcher at the Ins…

© 2025 Charles McKelvey

Substack is the home for great culture