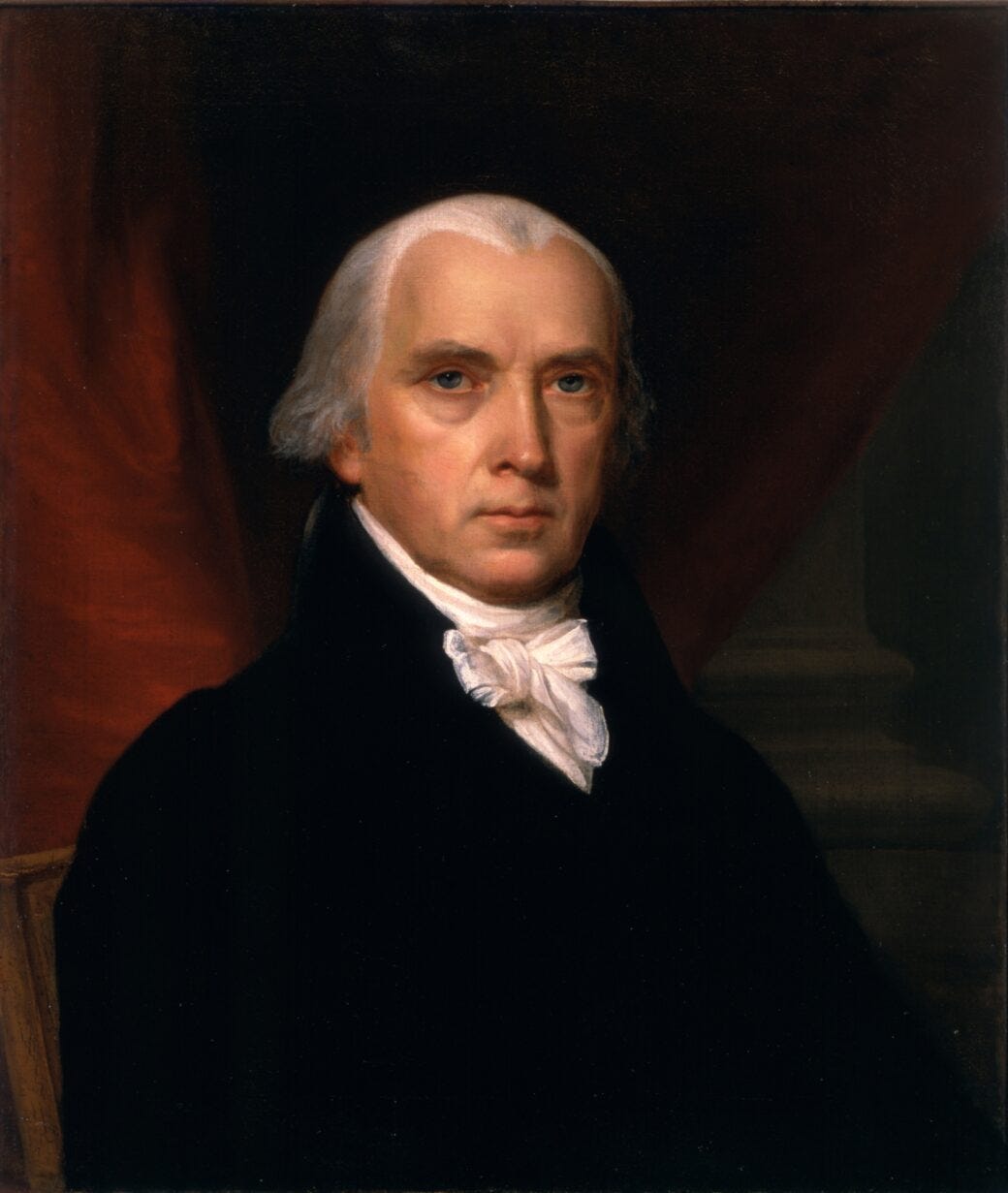

It may appear that James Madison and Fidel have little in common. But superficial appearances can be deceiving. In reality, both played leading roles, in political practice and in theoretical interpretation, in revolutions that defined their epochs, revolutions that are central to human progress.

The American Revolution declared its independence on a foundation of republican principles, and it launched an armed struggle to attain political independence in practice. When the original thirteen independent states experienced in political practice that the central government formed by the Articles of Confederation was too weak to defend and protect republican principles, they created a Constitutional Convention that debated and wrote a new Constitution, creating the institutions an…