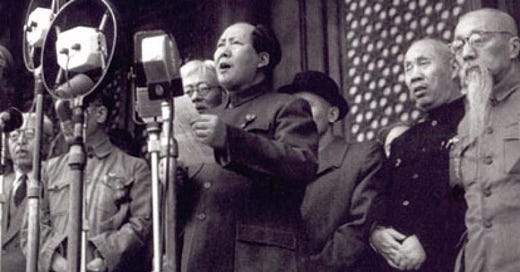

Mao: The foundation of China today

Since 1982, the collective and sustained judgment of the Communist Party of China has been that Mao Zedong made political errors in formulating and promoting the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. Nevertheless, the Party also has judged that Mao’s contributions to the revolution and the nation far outweighed his mistakes. He led the revolution to the taking of power and directed the revolution in power to a transition to socialism, which provided the foundation for the sovereignty of the nation and the modernization of the economy. China today stands on a foundation built by Mao.

The historical context: Mao and the Communist Party of China

In ancient and feudal times, the Chinese empire was one of the largest and most advanced in the world. And during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Chinese economy was advancing in technological development and economically expanding. However, not possessing an imperialist dynamic, the Chinese economy had no sti…