Moncada

A great and heroic act, seventy years ago today

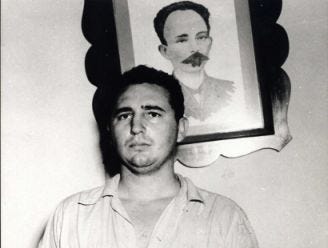

In a manifesto released on July 23, 1953, Fidel Castro, at the time a Havana lawyer known for defending the poor, called upon the people to “continue the unfinished revolution that Céspedes initiated in 1868, Martí continued in 1895, and Guiteras and Chibás made current in the republican epoch.” The revolution, he maintained, was the revolution of Céspedes, Agramonte, Maceo, Martí, Mella, Guiteras, and Chibás. This single revolution, having evolved through different stages, now was entering a “new period of war.”

The initiation of the new stage was proclaimed dramatically three days later, on July 26, when Fidel led an attack on the Moncada military garrison in Santiago de Cuba. The intention of the assault was to seize weapons for the launching of a guerrilla struggle in the mountains. The assault failed, and 70 of the 126 assailants were killed, 95% of them murdered after capture by Batista’s soldiers …