Neocolonialism and the New Imperialism

The persistent quest of the neocolonized peoples for true sovereignty

In my last commentary, I discussed the emergence of socialism with anti-colonial characteristics forged in practice from the colonial situation in Korea, Vietnam, and China, led by exceptional leaders (Kim Il-Sung, Ho Chi Minh, and Mao Zedong) who adapted the teachings of Marx and Lenin to the conditions of their particular nations. See “The conquered peoples seek a more just world: The emergence of socialism in the world of the colonized,” April 18, 2023.

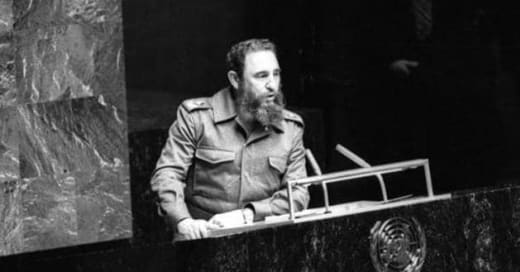

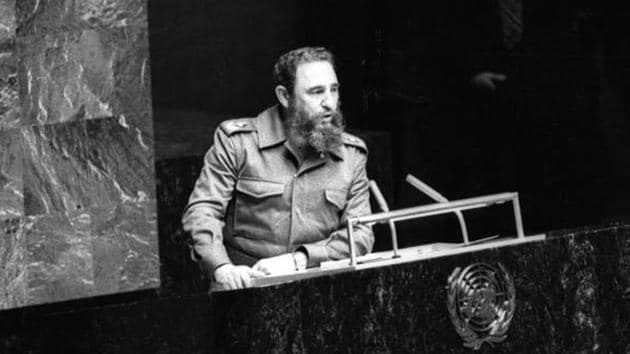

The emergence of socialism with anti-colonial characteristics was itself part of a larger anti-colonial people’s revolution in Asia and Africa that was initiated in 1919 and came to culmination in the period 1946 to 1963. Exceptional leaders emerged, such as Sukarno in Indonesia, Nehru in India, Nasser in Egypt, Nkrumah in Ghana, and Nyerere in Tanzania. The emergence of the colonized as political actors on the world scene…