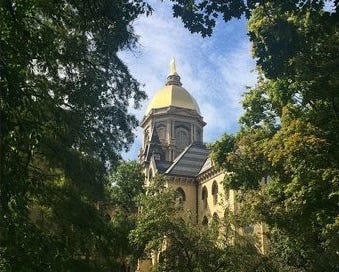

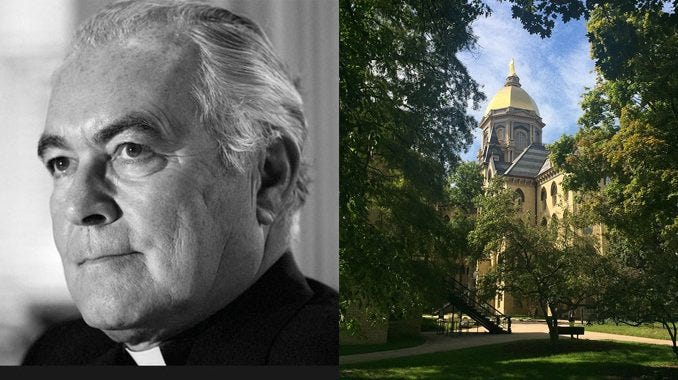

I have been a Catholic all my life, although in the last thirty years primarily as identity rather than actual practice; and as a young man, I spent eleven years as a student and teacher in Catholic higher education. Reflecting my Catholic identity and in accordance with my desire to observe what is going on in all areas of society, I subscribe to The Catholic World. There I came across an article by Conor B. Dugan reviewing a biography of Fr. Theodore Hesburgh, the well-known president of the University of Notre Dame from 1952 to 1987. The biography, entitled American Priest: The Ambitious Life and Conflicted Legacy of Notre Dame’s Father Ted Hesburgh, was written by Wilson D. Miscamble, a member of the Holy Cross Order and a history professor at Notre Dame.

The secularization of the Catholic university

Dugan reports that Miscamble delved into the subject of Hesburgh’s life in order to understand more deeply the ambiguous legacy of Notr…