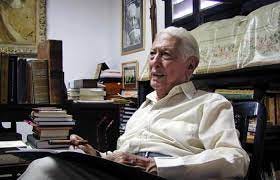

Cuba recently commemorated the 100th anniversary of the birth of Cintio Vitier, Cuban poet, critic, essayist, and novelist who died in 2009. The commemoration included a sixty-minute television news program devoted entirely to the author of Ese Sol del Mundo Moral (“That sun of the moral world”), originally written in 1974 and republished and reprinted in several editions. The book is a history of the Cuban Revolution, but more than a history, it is “an essay of philosophical reflection on the Cuban Revolution,” as was observed by Abel Prieto, former Minister of Culture; a reflection that gives emphasis to the moral character of the revolution. Its central concept is that the morality of Cuban political culture, intertwined with the persistence of hope, was the base of the triumph of the revolution.

Prieto, who now is President of the Casa de las Americas, maintains that the book is more relevant to…