In today’s commentary, my intention is to make clear the evolving conceptualization of the African-American movement from 1917 to 1972, providing a foundation for my reflections in my next commentary on the period from 1972 to the present. In writing today’s commentary, I have consulted my 1994 book, The African-American Movement: From Pan-Africanism to the Rainbow Coalition.

The historic struggle for equality of opportunity

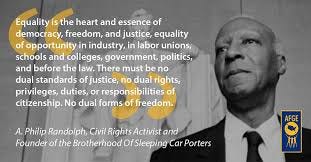

The primary intellectual tendency of the African-American movement from 1930 to 1968 was the attainment of equality of opportunity in America.

Black Americans first became a political force in the USA in the 1930s, when the black migration to industrial states, which began during World War I, enabled black voters to affect the outcome of presidential elections in key states in the electoral college voting system for presidential elections. In the 1930s, the black press (working at that time in separate black-owned newspapers in major cities) claime…