The lesson of the Cuban War of 1868-1878

The need for unity of purpose rooted in objective conditions

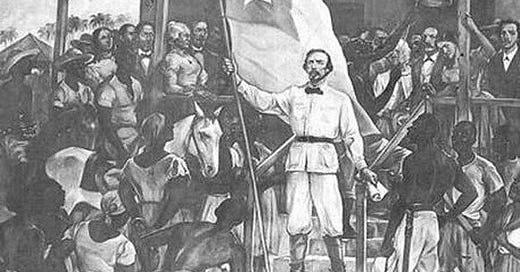

On October 10, 2024, in the Cuban online news outlet Cubadebate, there appeared an article by Francisca López Civeira, a well-known Cuban historian, on the initiation of the first Cuban War of Independence on October 10, 1868. On that date, Carlos Manuel de Céspedes declared from his Demajagua Estate in Manzanilla the launching of a war of independence from colonial Spain.

López informs us that prior contemporary events had been favorable for the pronouncement of independence. In 1866-1867, a reformist effort in Spain had failed, thus strengthening the independence cause. Conspiratorial groups emerged across the island, especially in the eastern and central regions. In September 1867, the Glorious Revolution resulted in the overthrow of Queen Isabella II, initiating division and instability in the Spanish government that would last sev…