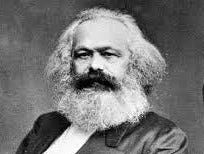

The scientific analysis of Karl Marx

A comprehensive synthesis from below tied to political practice

Marx forged a synthesis of British political economy and German philosophy from the vantage point of the worker. On a foundation of encounter with the emerging proletarian movement, Marx discerned meaning in human history, and he envisioned a future society established on a foundation of automated industry and characterized by versatile work and by the reduction of labor time. His work represented the most advanced formulation of his era, overcoming the idealism of German philosophy and the ahistorical empiricism of British political economy, and analyzing human history and capitalism from the vantage point of the exploited and dominated class. Marx’s formulation was a threat to the capitalist class, because it was an emancipatory paradigm, pointing to the transition to a socialist society through the political action of the working class.

Marx’s achievement established the possibility for significant advances in understanding human societies and political-economic systems…