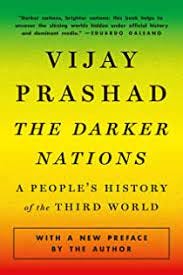

The Fifteenth Anniversary Edition of Vijay Prashad’s The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World (originally published in 2007) was recently highlighted online by the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism. The Fifteenth Anniversary Edition is identical to the 2007 edition, except that it includes a new preface, signed by the author in February 2022.

Vijay Prashad is director of the Tricontinental Institute for Social Research and editor of LeftWord Books. He is author of Uncle Swami: South Asians in America Today and The Poorer Nations: A Possible History of the Global South (2012). The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World was chosen as a Best Nonfiction Book of the Year by the Asian American Writers’ Workshop and won the Muzaffar Ahmad Book Prize. Prashad lives in Santiago, Chile.