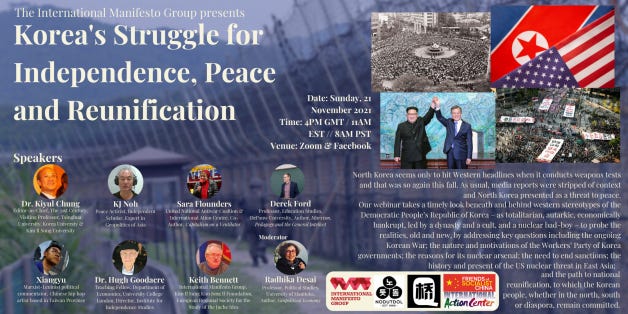

The International Manifesto Group sponsored on November 21 a Webinar on the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, seeking to look beyond the Western stereotypes of the East Asian nation as totalitarian, economically bankrupt, and a threat to world peace.

The International Manifesto Group, panelist Derek Ford observed, is indicative of a trend in the academic left, which he characterized as the emergence of “anti-Marxist Marxists.” He noted that when neoliberalism emerged, Marxists and other leftists looked at neoliberalism from the vantage point of its impact on the workers of the North. But now there is a new trend that looks at the world-system from the vantage point of actually existing socialist projects, which is consistent with Marx’s scientific method. Inasmuch as the nations constructing socialism are in the Third World plus China, this approach takes us to analysis of the impact of neoliberalism on the peoples of the world beyond the North.

The panel was mod…