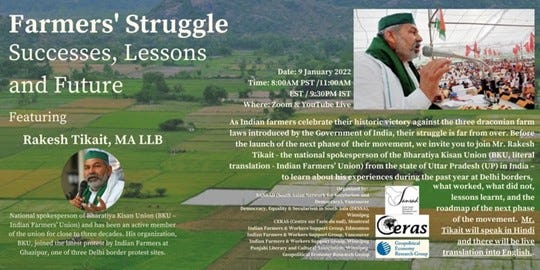

The Geopolitical Economy Research Group of the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, sponsored on January 9 a Webinar on the Indian Farmers’ Union (Bhartiya Kisan Union, BKU). Rakesh Tikait, the national spokesperson of BKU, discussed the 2021 victory of Indian farmers, whose sustained protest forced the government of India to repeal three draconian farm laws that the parliament had passed in 2020. The event was co-sponsored by: SANSAD (South Asian Network for Secularism and Democracy), Vancouver; Democracy, Equality & Secularism in South Asia (DESSA), Winnipeg; CERAS (Centre sur l’asie du sud), Montreal; Indian Farmers & Workers Support Group, Edmonton; Indian Farmers & Workers Support Group, Vancouver; Indian Farmers & Workers Support Group, Winnipeg; and Punjabi Literary and Cultural Association, Winnipeg.

The Context

In September 2020, the Indian parliament enacted, and the president signed, three agricultural laws. The new laws provoked mass protests by fa…